All of the WB countries (except Kosovo) are part of the “16+1” platform for cooperation. In the last several years, the cooperation between China and the group of sixteen post-communist countries – dubbed CEE16 – with whom the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs has established a Secretariat for cooperation (CEE16+1) has been a major breakthrough in the overall China-Europe relations. The cooperation formula consists of building political trust without dealing with high politics, facilitating cultural exchange, with the end goal being boosting economic cooperation.

Initially caught off guard, the CEE16 have gradually come to embrace the cooperation which was proposed by China. Most of them had demonstrated a chronic thirst for foreign direct investments (FDIs) which are considered a main driver of the economy that has not been matched adequately. Moreover, the global financial crisis, and in particular the lowered economic prowess of the US and Western Europe, had effects on the region as well. Before the Ukraine crisis, post-communist Europe in general has also waned from the global debates as the attention has shifted towards other regions in the world (i.e. the Middle East and North Africa Regions (MENA)).

China, which has led a pro-active “Going Out” policy, identified an opportunity and initiated a new form of cooperation through making concrete steps towards its materialization by proposing the so called “twelve measures” in Warsaw in 2012. In 2013, first in Chongqing and then in Bucharest it has made significant amendments, by further “Europeanizing” the discourse and putting the focus on transportation infrastructure and regional approach. The recently adopted 2014 Belgrade Guidelines further deepen the cooperation.

On a diplomatic level, the overall relations between the CEE16 and China are deemed to be at a historical peak. In 2014, China celebrated 65 years of diplomatic ties with Bulgaria, Romania, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary and Poland. China considers their shared communist past, along with anti-Soviet sentiment, and the reform experience to be “a special advantage” that other partners in Europe do not possess. The WB have their own share of symbolic capital in the 16+1 relations with Albania being remembered as the sole country that embraced Maoism in the 1960s - despite the later split and the former Yugoslavia is remembered as a successful socialist market economy and inspiration for the reform process.

Southeast Europe matters for China’s global vision. In the last several years, China’s “Going Out” approach has come to complement a new geopolitical orientation named New Silk Road (NSR). The ultimate goal of the NSR is to improve the connectivity within and between Asia, Europe and the rest of the world by land and sea, while boosting the economy of China’s westernmost and least developed areas. In the discourse of Chinese scholars, the role of the CEE16 is seen as crucial in “facilitating the construction” of the NSR, Europe-Asia relations in general, and China-EU relations in particular. The WB is of particular importance as it is at the crossroads between the Mediterranean and the Eastern European frontier,

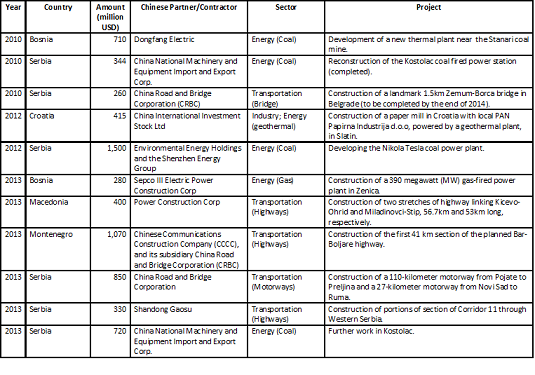

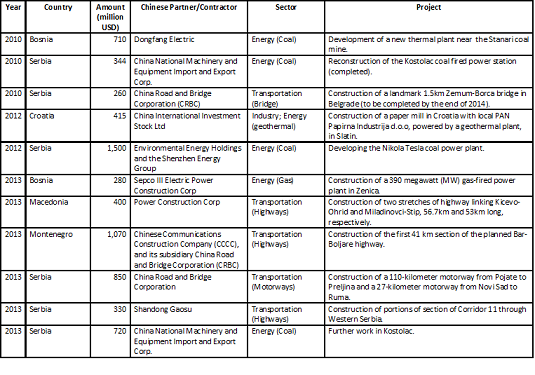

While the so called “Eurasian land bridges” which constitute the continental Silk Road Economic Belt have their final destinations in the Western European markets, a significant portion of their infrastructure and trade corridors are planned to branch throughout Eastern, Central and Southeast Europe. Some of the land bridges are already a reality, as working connections already exist between different cities in China and Europe. While the NSR is a concept with Chinese characteristics (meaning there is no definite blueprint, timetable nor anyone to specifically ask about it), it is clear that it will certainly involve some of the countries of Southeast Europe. It is important to note that the “Belt” component aims to transform frontiers into bridges and restore the physical economy on the way, something that could resonate well in South Eastern Europe (SEE). In the SEE region, China so far has invested primarily in energy and road infrastructure.

The Maritime Silk Road has important nodes in the Mediterranean Sea, in particular in the Piraeus port in Greece, which has become “the world’s fastest growing container port” after being given under concession to the Chinese state-owned enterprise COSCO in 2009. The cooperation between China and Greece was placed on the fast track after the recent back-to-back visits by Premier Li Keqiang and President Xi Jinping ( an unprecedented occurrence in the history of Chinese diplomacy), and the announced deals regarding the Port of Thessaloniki, as well as Greece’s railroads and airports. The Chinese vision is to ultimately link the Greek ports to the Central European markets by land and this is the context in which the landmark Budapest-Belgrade high-speed railway has been framed. It is to be expected that it will be the first leg of a trans-Balkan high-speed rail (Macedonia also took part in signing the agreement). Aside from the initiative of new railway from Budapest to Athens; there has been a growing interest in centuries-old proposals for inland waterways.

European but Non-EU countries are of “special importance” for China. China perhaps sees new momentum in the WB, as the new European Commission does not seem to be too concerned with the enlargement prospects. These countries, and in particular the WB, are seen as more “flexible” in the sense that their legal and political frameworks are not yet fully compliant with those of the EU . Furthermore, they do not need sovereign guarantees to be able to use Chinese credits, and given their relatively low GDP per capita, they are eligible to receive Chinese developmental aid. As such gaining an economic foothold in these countries at this moment is much easier than gaining it in EU member-states. Moreover they can serve to be a testing ground for Chinese enterprises, and once these countries join the Union, China could have already gained a significant presence inside it.

This then poses the question of the potential interplay between growing cooperation with China and the EU enlargement. China is perhaps the most divisive issue in EU foreign policy, with the member states racing for deals with Beijing, while slacking on the priorities of the Union (i.e. Germany and its “Special Relationship” with China). Frustrated by the failure of EU to speak with one voice on China, Brussels has so far been sour on the 16+1 cooperation – especially because of its institutionalized form. However, China regardless of its radical pragmatism has maintained a firm position that the EU as a whole matters more and that 16+1 should be seen as subordinate relationship. It has been underscored that even with the “special advantage” of being outside of the EU for the time being, the prospects of WB countries for a more elaborate and truly economically beneficial China relationship depend on their European future. In this sense, Beijing sees the WB as a part of Europe already (perhaps more than some Europeans or WB elites do).

One connected dilemma is how China as a new actor with growing linkages and leverages in the region can affect political change, especially with regards to the rise of authoritarian figures such as Gruevski or Vucic. Unlike US and the EU it has no moral concerns or many political strings attached to its economic packages. It cooperates with democracies and non-democracies alike and does not formally encourage diffusion of its own model. After all, the world sees China’s main strength in the 21st century to be in the realm of political economy, rather than politics specifically, which is something that scholars and officials in Beijing are well aware of.

Finally, can the Chinese perception of the CEE16 and in particular the WB reveal something that has been overlooked in the SEE area studies? While the official discourse on CEE16 and the WB in Beijing is very optimistic, Chinese scholars and practitioners are skeptical about several issues. First, they see the CEE/WB political elites as opportunistic and unreliable. They remember how the post-communist countries in the 1990s emphatically embraced the West and completely severed their ties with China on “anti-communist” grounds - their severance was worse than that of the West itself (Macedonia even went on to recognize Taiwan in 1999); however they completely reversed their stance when a strong China emerged and offered them economic cooperation. Secondly, they believe that neoliberalism CEE/ Balkan style is in a way a much “lazier” system than socialism was – as the regional elites have maintained their role in the economy but now put forth less effort into substantial economic reforms instead hoping for rich foreigners to fulfill these duties. Ironically, it was communists who built the old railways in the Balkans, and it will once again be communists who build the new ones. Finally, there is still insufficient regional cooperation for the liking of the Chinese, as national elites have been cognitively confined to their national borders and often have antagonistic positions based on the diverging “national interests” of populations the size of small Chinese towns. One of the leading young scholars working on the Balkans at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences has written on the history of (socialist) cooperation and pan-Balkan federalism, only to be disappointed how little of that spirit is part of the regional discourse today. Let’s hope that the Chinese trains help us facilitate regional cooperation and ultimately help us get to a better place soon.