The first data on the costs and political changes which would arise from Ukraine’s accession to the EU, could sway voters in the Union. This further diminishes the possibility of Western Balkan countries eventually joining the EU, even though the cost thereof is almost insignificant compared to the case of Ukraine

As soon as the Eastern Bloc collapsed, the western members of the European Union greedily took over the economies of Eastern and Southeastern Europe. Cheap labor and new labor markets came in handy at the time. The same will happen to Ukraine after the guns fall silent. However, EU membership – or at least access to more non-refundable development aid – is less likely to happen when it comes to Southeastern European candidate countries in the foreseeable future. In the case of Ukraine, membership remains almost unthinkable despite the many geopolitical musings in the Union.

In the first week of October, data from an unpublished analysis commissioned by the European Council was "leaked" in Brussels. If the rules valid for the existing budget from 2021 to 2027 were to be applied to the Union enlarged by Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia and the "Southeast European Six" (Serbia, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Albania, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina – SEE6), EU expenditures should increase by 256.8 billion euros in the next seven-year budget. Of that, Ukraine would receive 186 billion or about 72.4 percent. (Turkey is excluded from the calculation, as apparently, after a quarter of a century of negotiations, it was written off as a candidate.)

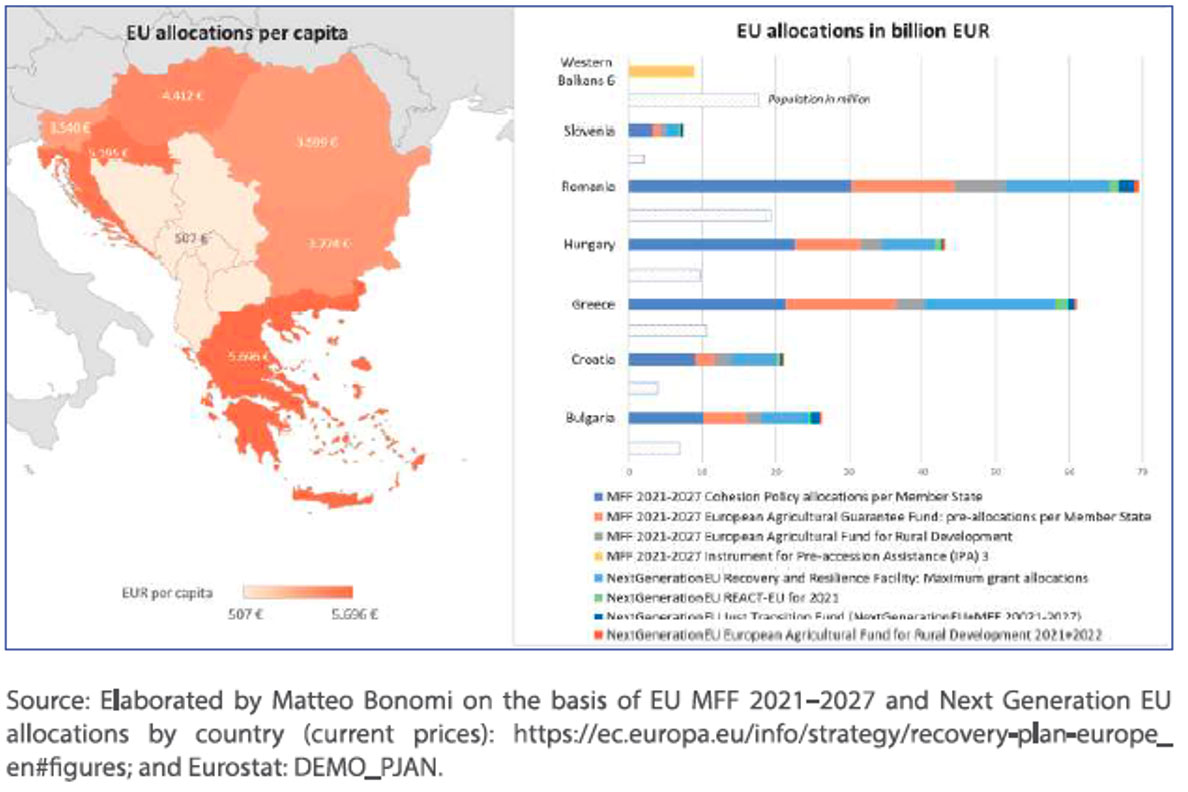

EU allocations to south-east European countries, 2021-2027

Source: Elaborated by Matteo Bonomi in IAI policy paper In Search of EU Strategic Autonomy: What Role for the Western Balkans?

Source: Elaborated by Matteo Bonomi in IAI policy paper In Search of EU Strategic Autonomy: What Role for the Western Balkans?

With nine new member states, the budget would increase by 21 percent to 1,470 billion euros, according to the analysis. That is about 1.4 percent of the gross national income of all 36 countries. All current member states would pay more and receive less from the EU budget. The current members (EU-27) would receive about a fifth less in agricultural incentives. Currently the largest recipient of such subsidies, France, would fall to second place, behind Ukraine.

Richer countries such as Germany, France and the Netherlands would have to be significantly more generous. After the admission of the new nine member states, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Lithuania, Slovenia, Cyprus and Malta would no longer be able to receive money from the Union’s so-called cohesion funds (non-refundable development aid).

The first calculations are not final, but they are enough to cause a serious reconsideration of whether the EU could withstand the admission of such a large state as Ukraine, and one in such a bad state (which worsens every day of the Russian attack). One might overlook the fact that, in comparison with the Ukrainian "calculation" (around 43 million inhabitants, before the war), the possible expenses for the 15-17 million Western Balkans inhabitants are almost insignificant for the EU. Apart from that, its members already benefit significantly more from the candidate countries in Southeastern Europe than they spend on them.

The economic risks related to the possible enlargement are followed by several serious political doubts. The most complex question is what kind of decision-making can function in the EU with an increased number of small and often mutually hostile member states? Relatedly, how could the European Parliament, the European Council and the European Commission function with this many members of the Union? And: what could replace the current enlargement policy (which, obviously, failed), which would ensure that the entry of potentially all nine new members does not "topple" the EU?

Security interests drive EU enlargement: European Union (as it is called since 1993, formerly the European Community, created in 1957) has always wanted to "absorb" as quickly as possible the countries where dictatorships have ended. The state of the rule of law was not overly looked into, nor were many other conditions set when Spain, Portugal and Greece were accepted as members in the 1980s. It was assumed that the expansion of the EU would prevent the new democracies from returning to their violent past.

In the 1990s the renamed EU took under its wing the impoverished and politically hectic Eastern European neighbours who had just been released from their half-a-century long Soviet grip. In Southeastern Europe, France ensured that another two former Soviet dependencies – Romania and Bulgaria – could also join the EU in 2007. Paris was dissatisfied because of the fact that the other new members, including Slovenia and Croatia, were now under Germany’s influence. All in all, the benefit of the "opening" of the East was invaluable. Military contact with Russia shifted more than a thousand kilometers eastwards. New markets were opened, as well as access to the necessary workforce sources. Security and economic interests of Western European countries have always determined the speed and direction of the EU’s enlargement.

Similarly, the Russian attack on Ukraine led the EU in 2022 to grant Ukraine and Moldova the status of accession candidates. A surge of fresh enthusiasm for enlargement has revived the discussion of potential candidates in Southeast Europe.

Or least it reminded of their longstanding uncertainty – after 2013, when Croatia joined, EU enlargement stopped. On the other hand, Albania, Montenegro and North Macedonia were accepted into NATO a long time ago and without hesitation. The Atlantic military-political alliance thus "surrounded" the remaining crisis hotspots in the region, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia with Kosovo. At the same time, it cut off the possibility of Russia spreading its military-political influence to the Adriatic.

With nine new member states, the EU budget would increase to 1,470 billion euros, with all current members paying more into the common budget and receiving less than before

The "Remaining Six" in Southeastern Europe are not only surrounded by NATO and the EU, but are also predominantly economically dependent on the Union. Two-thirds of trade in the region is with the EU, primarily with Germany and Italy, while the region's share in EU’s total trade is only 1.4 percent.

The SEE6 group had a trade deficit with the EU of around 28 billion euros in the last three years alone. During the past decade, the deficit surpassed one hundred billion euros. Significant part of the exchange consists of intermediary products ordered by parent companies located in the EU. Many companies in the EU have established production facilities in SEE6 due to geographical proximity, cheap labor, tax benefits, high government subsidies and other incentives for investment. The state of human rights and democracy in the region had no particular impact on the arrival of foreign investors. Nor, as research shows, have foreign investments significantly accelerated social and economic development.

Investments mainly come from the EU and largely shape the industrial and technological development of post-communist Europe, including the Balkans. Also, most tourists come from the EU, their consumption being an important source of income for the region, thus largely affecting the service sector, too. IT services are mostly commissioned from the West. The EU is also the main destination for mass labour migration and brain drain from the region. Through trade deficits, loan repayments, cheap services and, most importantly, through the loss in human capital, the countries of Eastern and Southeastern Europe, including future EU members, are transferring considerable wealth to Western Europe. This contributes to the ability of EU member states, especially in Western Europe, to remain competitive on international markets and to sustain a high standard of living.

Human capital outflow to the EU: The realization that a better standard of living for them and their children would not come even in the distant future encourages many citizens of Eastern and Southeastern Europe to migrate to the West. In a recent report, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) stated that the rate of emigration from SEE6 increased by 10 percent over the past decade and that in the meantime about a fifth of the region's population moved to live abroad. In 2020, the first year after the pandemic, the number of departures was lower than in 2019, when it exceeded 250,000, but the outflow is still very pronounced. According to Eurostat data, more than 169,157 people legally emigrated from the region in 2021, and received their first residence permit in the EU – 55,085 from Albania, 44,091 from Serbia, 20,398 from Kosovo, 33,144 Bosnia and Herzegovina, 14,176 from North Macedonia and 2,265 people from Montenegro.

One of the reasons is that personal income in Eastern and Southeastern Europe, despite the process of comprehensive economic integration with the EU being ongoing for three decades, has remained significantly below the EU-15 average. An analysis by the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies from 2021 showed that in the two previous years, the average monthly gross salary in the EU-15 was four to five times higher than in the countries of the Western Balkans (graph number 1).

Average Monthly gross wages in EUR (purchasing power standard)

Source: Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw), 2021

Source: Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw), 2021

Connecting with the EU has so far led to greater prosperity and better economic prospects only in the countries of Southeastern Europe that have become EU members. Still, most of “new” EU members have not caught up with the west of the continent, even the former East Germany. Non-refundable development aid from the EU is crucial. Only in the case of new EU members in Southeast Europa has it reached a macroeconomically relevant level. The rest of the region is stagnating or lagging behind. Kosovo and Albania are still the poorest areas in Europe, the same applies to Moldova. Under existing conditions, SEE6 cannot come anywhere close to the average living standard in the EU it.

In fact, since the EU will inject up to eleven times more grants and soft loans to its member states in Eastern and Southeastern Europe within its current seven-year budget, Western Balkans will be lagging behind at an even quicker pace in the coming years.

Source: the original graphic was created by the Group of Twelve, 2023

In Germany and other most influential EU countries, there is no apparent intention to increase financial solidarity with the candidate countries. Quite the opposite: the first data on possible additional costs for Ukraine, on top of all the grenades and tanks, will stimulate even more frugality. In addition, there will be stronger demands to politically ensure that EU enlargement does not cause a collapse of the Union itself. Germany and France are already making the accession of new members conditional on the abolition of unanimous decisions in the EU on foreign policy and other important areas. The goal would be to preserve the "ability to decide" if the membership is expanded. This requirement will block further EU enlargement as weaker member states are unlikely to give up their veto rights, the most effective way of pursuing their interests in the Union.

Germany and France condition the accession of new members on abolishing unanimous decisions on foreign policy and other important areas, in fear that EU enlargement could cause the Union’s collapse

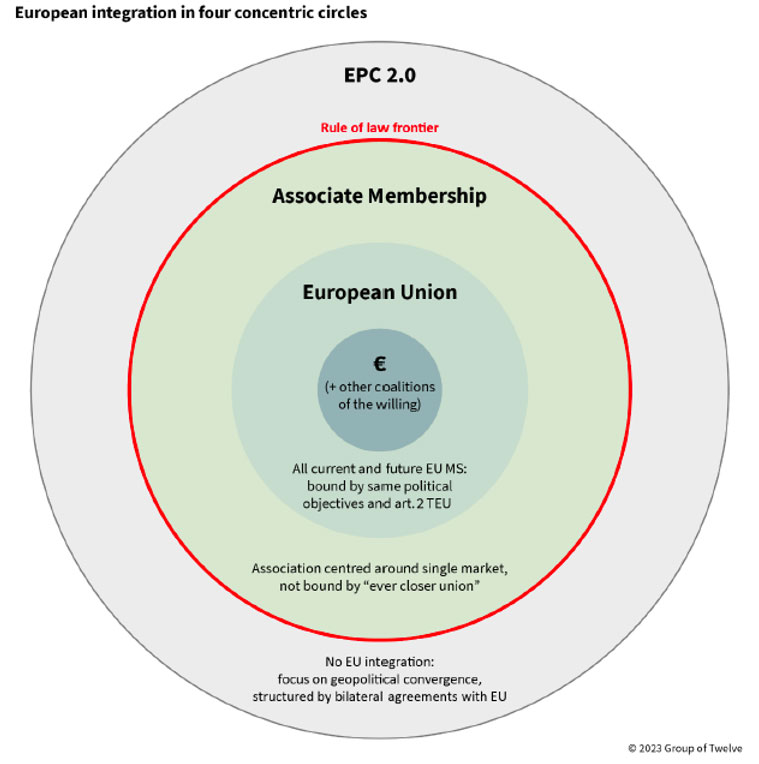

At the same time, old ideas are being recycled – at the request of the Ministries of Foreign Affairs in Berlin and Paris, in recent months a working group of selected political scientists proposed the direction of "institutional reforms" in the EU. The outcome is what already exists in reality: several concentric circles of integration (graph number 2).

Observing such schemes, one gets the impression that their supporters would prefer the future to resemble the past so that nothing would change for those who are in the center of that circle of European integration. Maybe the future will indeed look like this on the paper of political resolutions and agreements. In reality, people will continue to emigrate in pursuit of a better life that is constantly beyond their grasp, despite all the pretty words about the bright future of the European continent, which will begin any minute now, as soon everyone makes an effort to do the "necessary reforms". What will Eastern and Southeastern Europe resemble, politically and economically, when a significant part of the population has moved out, is unfathomable. Certainly not the "flowering landscapes" envisioned by Helmut Kohl, chancellor at the time of German unification.

(A version of this text was published in the Belgrade weekly “Nin” on 12 October 2023.)