Of course in Bosnia constitutional law is used as a weapon to fight for political gain. As constitutional reform has remained elusive, politicians have resorted to constitutional litigation to ‘update’ the Constitution. Valery Perry suggested that strategic litigation remains ‘the most effective weapon’ for incrementally changing the Bosnian Constitution. She imagines a plethora of cases to unwind Bosnia’s Constitution. Izetbegovic’s referral on the constitutionality of the Serb national holiday is but one of these cases for fighting institutionally sanctioned ethnic discrimination in Bosnia through the means of constitutional law.

However, the quest for a Bosnia in which all constituent peoples are equal on the entire territory of the state may well transcend ethno-political divisions. Serb and Croat politicians referred cases to the Court in which they demanded the Court to protect the right of their communities by invoking constitutional and human rights law. Following a request by a high ranking Bosnian Serb SNSD politician acting as the Deputy Chair of the Bosnian Parliament, the Constitutional Court had ruled in 2005 that Serbs have to have equal minimum representation as other constituent peoples in the municipal assembly of Sarajevo. Following a referral by the Croat caucus in the House of Peoples, the Court declared in 2009 that the Mostar election law violated the principle of democratic equality. An implementation of the Court’s ruling would empower the local majority of Croats, which has led the SDA to block an agreement on the issue for the last seven years. Mostar’s Mufti denounced the Constitutional Court decision as aiming to accomplish “all of that which failed to be achieved by the war and ethnic cleansing.” The Court counters these accusations of partiality by often finding a constitutional violation in both entities. It declared the coats of arms of both the Republika Srpska and the Federation of Bosnia-Herzegovina in violation the Constitution. In addition, the Court found that the flag of the Federation but (oddly) not the flag of the RS as unconstitutional. The broader point is: constitutional law is used successfully as a weapon by all constituent communities or even individual actors (such as Sejdic-Finci, Zornic, and Pilav at the Human Rights Court). There is nothing wrong with that: it is much better and civilized to submit controversial issues to an arbitration tribunal such as the Constitutional Court rather than engage in aggressive political rhetoric or even fight it out.

Marika Djolai finds that the timing of Izetbegovic’s referral is calculated to maximize his political gain: “Why did he wait for more than two decades to challenge the Day of Republic Srpska, despite his constant presence in BiH politics since the 1990s?” The referral against the Law on Holidays started around a decade earlier. Izetbegovic could not have submitted the case, because he did not hold an institutional position that would have allowed him to do so. It was one of his Bosniak predecessors at the state presidency, Sulejman Tihic, who challenged the flag, anthem and coat of arms of the Republika Srpska and of the Federation of Bosnia-Herzegovina. The national judges of the Court managed to find a compromise to advance the principle of constituency of peoples while shielding them from the political consequences of the decision. As said before, the national judges unanimously agreed to declare anthem and coat of arms unconstitutional, while ‘saving’ the RS flag. The British and French judge of the Court disagreed “after much heart- searching”; they would have declared the flag of the RS unconstitutional.

But compromise as an ‘exit strategy’ was not open to the Court in this case. The Court tried another ‘exit strategy’ – one that involved external authority and the factor of time. Back in 2013, the Court had asked the Venice Commission whether the RS National Holiday was unconstitutional. The constitutional advice giving body of the Council of Europe answered shortly later: the RS Republic Day gives rise to a violation of the Bosnian Constitution, the European Convention on Human Rights and the International Covenant on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. High ranking judicial officials at the Council of Europe told me that they had awaited a decision in 2014, but the Court postponed the decision until the end of 2015. The Court tried to buy time in this case, but sooner or later it needed to take a decision. The Court actually chose the timing rather well – it took a decision in a year (2015) when there were no elections in Bosnia-Herzegovina and with a following year (2016) where there is only one election (the upcoming municipal elections of 2 October).

Markus Tanner wrote that “almost every national holiday is ‘discriminatory’ once it is examined under some sort of constitutional microscope” – but this point misses the specificity of Bosnia. In a case which acts as a significant precedent to the present issue, the Court declared the RS Law on the Family Patron-Saints’ Days and Church Holidays unconstitutional. The Court ruled that the mentioned holidays reflect and exalt the Serb history, tradition, customs and religious and national identity only, imposing it upon the members of other constituent peoples. In the highly analogous present case, the Venice Commission and the Constitutional Court agreed that the principle of constituent peoples makes Bosnia a polity that is different from other countries: “The legal order of BiH … includes general clause on nondiscrimination, [which] affords a greater protection against discrimination than the European Convention i.e. a constitutional obligation of non-discrimination in terms of a group right.” The Bosnian Court shaped the principle of constituent people following a referral by Izetbegovic’s father, Bosnia’s war time leader and member of the presidency Alija Izetbegovic. As Bosnia’s three constituent groups have to be treated as co-equals all over the state, it is perfectly clear that the Bosnian Serb National Holiday is unconstitutional. Not only the international judges, but an overall 7-2 majority of the Bosnian Constitutional Court came to this conclusion. Taking account of the Court’s prior case law, there was no way it could have upheld the Serb holiday [without compromising on principle]. The reasoning could have been nuanced. One option would have been to suggest alternatives to the current way of celebrating the RS national holiday. This was recommended to the Court by the Venice Commission but it run at the risk of being interpreted as an even more political decision of the Court. A second option could have been to refer exclusively to the contested origins of the Republic Day rather than its religious character. The point is: considering the constitutional principle of collective equality of the three main groups throughout Bosnia, it is perfectly logical that the RS National Day was totally incompatible with the Bosnian Constitution.

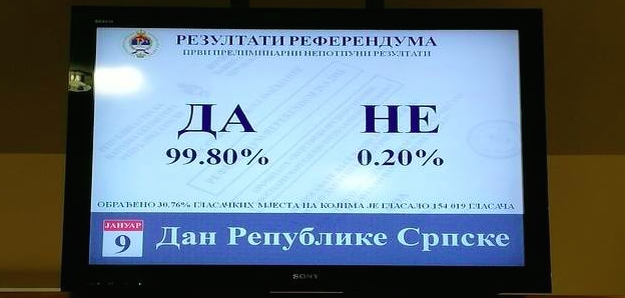

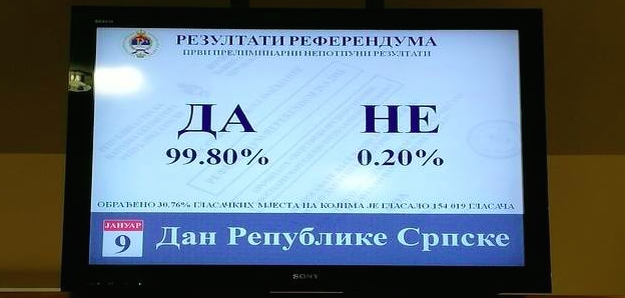

Djolai and concerned international observers seemed to take issue with the decision of the Court not to reconsider the case while at the same time suspending the referendum. Djolai wrote: “Despite the deepening crisis, the Constitutional Court of BiH remained firm on their decision. At the same time, the Court upheld the appeal of Bakir Izetbegovic to prohibit the referendum, although the mechanism of putting this in practice is still not clear.” I disagree with this argument. Article 68 of the Rules of the Court allow the Court to review a decision already taken “in the event of discovery of a fact which might by its nature have a decisive influence on the outcome of the dispute concerned and which, when a decision was taken, was unknown to the Constitutional Court and could not reasonably have been known to the party…” The RS National Assembly in its request for review did not even try to present any new facts. If the RS really wanted the Court to find a way out, it should have presented the Court with new arguments. It also could have requested the Court to give the RS more time to implement the judgment, and maybe the Court would have extended the deadline for implementing the ruling. The RS did not do anything of that because it is perfectly comfortable with the opportunity of political gain that the referendum has created. Contrary to what Tanner claims, the RS that escalated the case by calling a referendum on the Court’s ruling and not the Bosniaks. In what seems to have been a unanimous judgment, the Court rightly rejected this half-hearted appeal of the RS.

It is also incorrect to state that the Court ‘upheld the appeal of Bakir Izetbegovic to prohibit the referendum’. What the Court did is to say that the referendum “raises several serious and complex issues both with regards to the admissibility of the request and the merits”. It temporarily suspended the referendum pending a decision on admissibility and merits of the case. I believe that no one can take issue with the reasoning of the Court that “serious and irreparable detrimental consequences for the enforcement of the decision of the Constitutional Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina.” According to prior case law of the Constitutional Court and its rules, an interim measure will be granted “if irreparable detrimental consequences could occur or if it is in the interest of the parties and appropriate for the proceedings”. If overwhelming popular majorities vote down the decision of the Court, it is perfectly clear that this will mean that the decision will not be enforced. Irreparable harm is done to the Court by way of submitting its ruling (which is final and binding) to referendum. More than a year ago on the lines of this blog I argued that the Court should halt a Bosnian Serb referendum, but this is not (yet) what the Court decided. What the Court unanimously said is: we will grant the interim measure to temporarily halt the execution of the referendum, so that the Court can consider all relevant legal arguments, and then take a decision on admissibility and merits. The decision of the Court actually created a small window of opportunity to delay the referendum.

The Constitutional Court is an indispensable institution for enforcing the Dayton Constitution. Diplomats and analysts should not blame Bosniaks for submitting requests to the Court or the Constitutional Court for deciding it. The Constitutional Court has decided similarly sensitive topics in the past, starting with the decision on the Constituent Peoples in 2000. Although many shortcomings remain, that decision was crucial for making Bosnia and its entities a fairer and more inclusive political space. Reform of entity constitutions in line with that judgment would have perhaps never seen the light had the High Representative not stepped in. What is different in this case is not who appealed to the Court or which decision the Court took, but the fact that the Europe and the US are too weak to counter this breach of the Dayton Peace Agreement. The emperor has no clothes, but it is not the Constitutional Court that said it.