In 2016, while the country is experiencing its second spring, hopes for systemic change are on the rise. The political crisis offers an opportunity to bridge interethnic divisions in Macedonia and to bring about a more integrated society. Until now, the majority of the political parties have used ethno-national mobilization and have stimulated emotions to gain votes, while sidelining issues such as unemployment and the resulting brain drain, corruption, and an ever-declining democracy. The question is whether ethnic Macedonian and ethnic Albanian parties are ready to offer alternatives to their citizens or whether individuals, with their actions, can stimulate the reformulation of interethnic relations?

Ethnic divisions and the political crisis

Competition between political parties has mainly remained within the ethnic Albanian and the ethnic Macedonia blocs, with a weak gray zone in the middle where there are attempts to bridge ethnic divisions. Although new ethnic Albanian political parties have fractured from the two major parties, such as Uniteti (a splinter party from BDI) and the Movement for Reforms in PDSH (a splinter party from PDSH), they have also kept their criticism within the ethnic Albanian bloc and occasionally against the Prime Minister of the country. In addition, there is a strong division in the public discourse over ethnic Albanian and ethnic Macedonian interests, which reinforces the ethnic division. One area where the distinction between ethnic interests is made clear is in relation to the political crisis.

The two major Albanian parties do not want to support the protests, while the Movement for Reforms in PDSH organized a separate Albanian protest, deciding to act separately from the other Albanian opposition parties. These parties argue that Zoran Zaev and SDSM have failed to relate to Albanians or to gain their trust. The campaign “Truth for Macedonia” tried to tempt Albanians by translating placards, but it never demonstrated that it understands the Albanian constituency or their worries. It must be noted, however, that Mr Zaev has made repeated calls for Albanians to join the protests. So far, a number of smaller parties (e.g. Levizja Besa, RDK) have officially supported the protests, and some prominent members of Uniteti have joined as well. However, the boycott of the major parties, the separate protests and half-hearted support of the smaller parties shows that Albanian parties and their constituencies still lack trust in the opposition. On the other hand, Albanian parties fail to acknowledge that their role and positioning in the crisis will be an indication for the future of this ethnic group in Macedonia.

The recent trend of labelling the protests as “the protests of Macedonians”, on social media and elsewhere, by both members of Albanian political parties and constituencies, is worrying. It indicates that there is a deep misunderstanding of the state of affairs as a result of ethnic divisions. They present the notion that there is a difference between Macedonian and Albanian problems, and the protest by the Movement for Reforms in PDSH was a very clear representation of this view. Notwithstanding that this difference might apply to discrimination and representation of minority groups; it does not relate to the widespread corruption and decline of democracy, which are the issues being protested against. The fact that Albanians in Macedonia feel that they are external to these problems shows that the implementation of the Ohrid Framework Agreement and the ensuing reforms have done little to truly integrate Albanians. In fact, the rhetoric of ethnic Albanian parties is proof that segregation has continued and that the implementation of the Ohrid Framework Agreement is just checking boxes.

Future perspectives: To protest or not to protest?

If the ethnic Albanian parties do not join the protests and give strong support to the rule of law and restoration of democracy, then they diminish their future political potential. They will be included in power-sharing; however, it is likely to be pro-forma and very much as it is now. Although until now the Albanian parties have seemed to satisfy the wishes of the international community, they do so at the risk of alienating their constituency. The community they claim to represent is treated as external and therefore peripheral. Worst of all, the citizens themselves are deprived of their agency in favour of waiting for the parties to solve their issues in an environment where all parties have proven to do the opposite.

If the Albanians, as individuals, decide to join the protest in greater numbers, there will be two great advantages to their position in the future. First, by attending the protests Albanians will develop a closer understanding of how the current political crisis affects their life; and second, it will give them bargaining power in the future. By attending the protests, Albanians will be able to make the argument that they, too, were in the streets, pushing for a more democratic state and for political changes. They can make the claim that they were equal partners. They might not change the leadership of ethnic Macedonian parties, neither will they change their politics, however they will change the position of Albanians. They will attain more ownership and will increase their capacities to influence the setting of agendas. If Albanians join the protests, then their major parties (BDI and PDSH) will reconsider their role and position in the current crisis. For example, BDI might decide to leave the government, or alternatively, BDI and PDSH may declare that they will not participate in the June elections, or they may decide to join the protests as well. This will empower the forces pushing for democratic change in Macedonia. Then the crisis will be redefined. The main division will be between political forces struggling to maintain a corrupt authoritarian regime on the one side, and political forces fighting to restore democracy and rule of law on the other. At the moment, BDI and PDSH claim to sit in the middle, while colluding with the regime.

For Albanians it has always been important to be considered equal citizens. Now they have an opportunity to attain that status by themselves, without a proxy. Ownership is powerful: the feeling of having a stake in the state of affairs demonstrates belonging to the state, which can no longer push individuals into being second rate citizens. It is most important for Albanians to have a voice at the table opting for their integration into the future society in Macedonia, and not the continuation of the ethnic separation of powers.

Herein lies the grey zone where ethnic division are/can be bridged. This space can also improve ethnic relations, but it has been only temporarily occupied by political parties. The new ethnic Albanian parties, which have still not been tested in elections, have the potential to bridge ethnic divisions if they do not adopt overtly nationalist or ethnic politics. However, these parties seem to be closer to the logic of the bigger parties: to preserve the centrality of ethnic politics. In general, these parties have turned out to be poor copies of their mother parties, which is unfortunate. For example, in recent interviews the leader of the Movement of Reforms within PDSH has often appeared more nationalist than BDI, just like the position of PDSH. In the Macedonian bloc, Levica, a newcomer party, seems very sensitive regarding representation of ethnic diversity, and SDSM has made several attempts in the past to bridge ethnic divisions; however, with limited success.

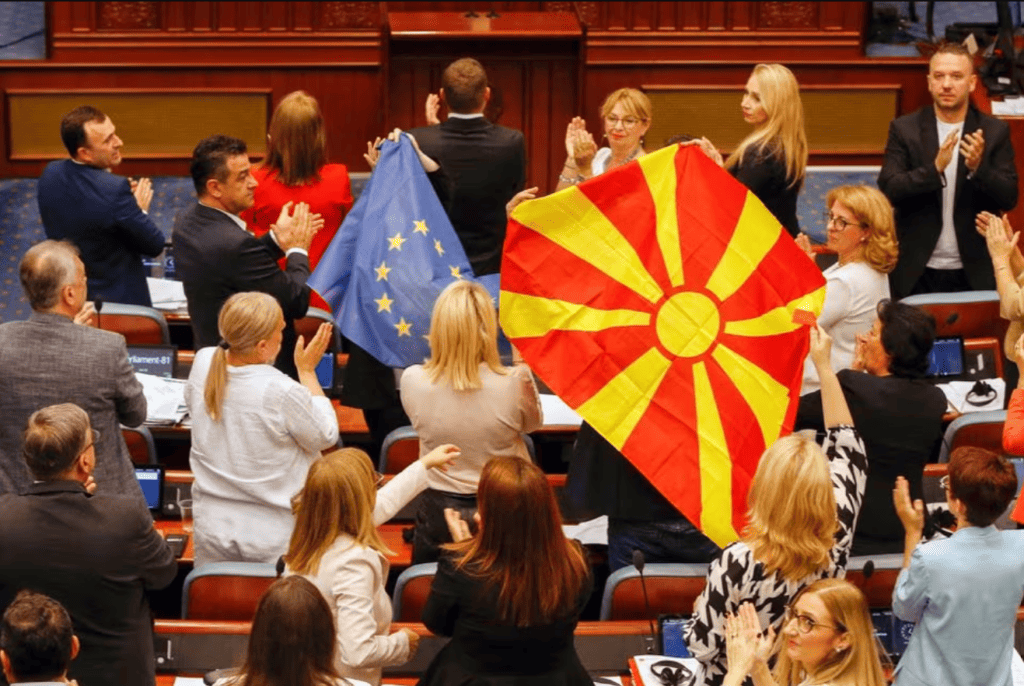

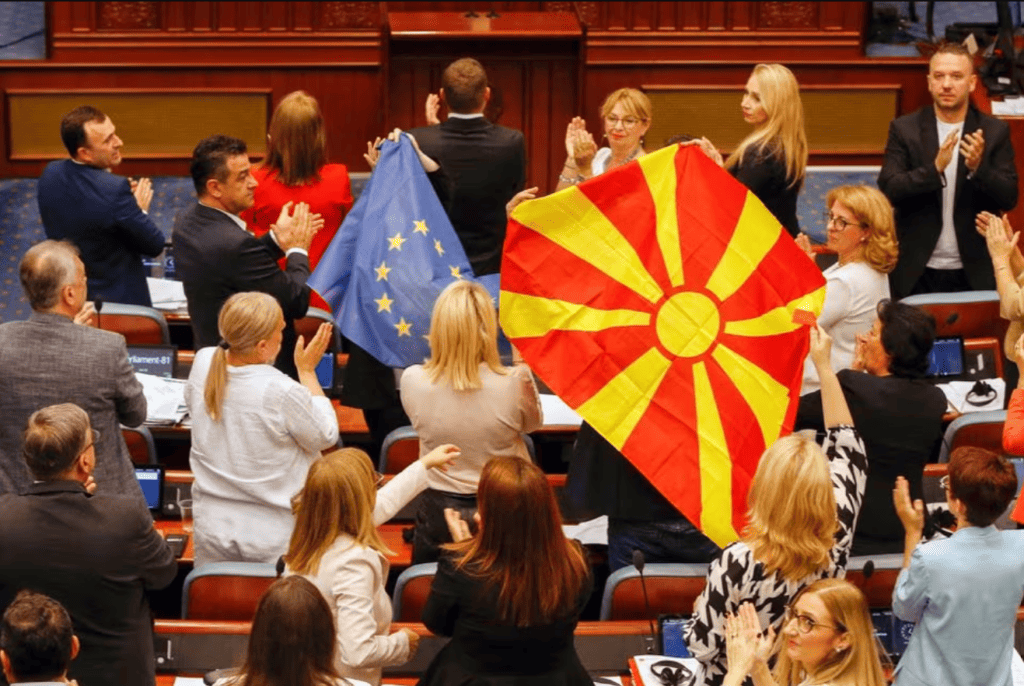

For now, the future of interethnic relations in Macedonia seems unclear; they may improve or worsen. There are two paths and two main agents. The paths are that of preserving ethnic divisions and that of bridging ethnic divisions. The agents are the citizens and the political parties. At the moment, it seems that it is the citizens that bear the power to create new interethnic relations and redefine the public space and rhetoric. The way to do this is to start attending the protests and to create a present - if not a future - where all citizens of Macedonia share in the country's fate and work together to build its democratic future as equal individuals.